The Law Enforcement – Designated Marksman Rifle project.

The Law Enforcement – Designated Marksman Rifle, or LE-DMR, is a project we’ve been working on since before Zero Theory existed. It is an adoption of the military concept of the Designated Marksman Rifle (DMR) to the law enforcement context. LEO’s have been carrying patrol carbines for years and their sniper counterparts have been carrying precision rifles for just as long. For most of that time, those two types of rifles were about all you had in law enforcement. But time and technology change things.

With the continuing refinement and maturity of the AR platform it is now feasible to build a short-barreled patrol rifle with sub-MOA precision capability. Improvements in technology and manufacturing not only make such a thing possible, but make it affordable as well. Precision capability can be built right into a patrol carbine. With the right training almost any agency can field certified and capable precision marksmen on every patrol shift. Agencies can now bring to bear the skills of a trained precision marksman with the immediacy of a first responder.

To that end, the original idea was to build a compact patrol rifle around a true match-grade barrel and top it with a versatile optic. We wanted the system to function as both a compact patrol carbine and a precision engagement weapon without sacrificing the essential characteristics of either. It should lack nothing for CQB and yet be fully capable of precision engagements at and beyond law enforcement distances. Whether conducting room-to-room clears, responding to an active shooter, or providing overwatch to an assault force, the LE-DMR should do it all and do it all well.

We’re well aware there aren’t many people building precision-oriented rifles with short barrels. A cut-down barrel means cut-down velocity, which is usually the opposite of what you’re going for with a precision gun. After all, almost everyone concerned with shooting precision is shooting long range whether they are a casual shooter, a precision rifle competitor, or a professional sniper. For this reason, precision shooting and long distance shooting have always gone hand-in-hand. Why then pursue a precision gas gun with a short barrel? Because precision shooting at “short distance” is a useful tool in the law enforcement context. This can be illustrated by examining the difference in mission profiles between precision shooters in the military and law enforcement.

Several years ago a member of the Zero Theory staff attended an Enhanced Sniper School for law enforcement officers hosted in the midwest. Most of the students were local and state police snipers, but there were also a couple Special Forces snipers in attendance as well. It was obvious how different an SF sniper’s job was from a law enforcement sniper. They carried long barreled 338 Winchester Magnum rifles with high powered scopes. Their mission focus was demonstrated by their equipment and they were obviously geared for long range engagements.

Interestingly, although they were not lacking in any skill to speak of, they were routinely out performed by some of the LE guys on short range precision exercises, such as 100-yard dot drills. After a while it seemed to bother them. One morning, just before a particular warm-up drill, they were overheard saying sarcastically “Alright! Let’s shoot some dots!” Obviously, they had had enough.

Without diminishing the above point, we should briefly give credit to those Green Berets. They were true marksmen, to say the least, and lacked nothing in terms of skill. They excelled in many areas. For one thing, they were fantastic on the stalking exercises. The instructors absolutely could not find them. Eventually the instructors were forced to end the exercise and have the Green Berets reveal their locations. Their performance was truly amazing.

Back on topic, that experience clearly illustrated how different the job of a law enforcement marksman was than a military sniper. Yes, we carry much of the same gear, speak the same language, and have similar training, but our missions are different. In law enforcement you can’t walk it in. You may only get one shot. It is a low probability, high consequence event. The shot will be cold, on demand, and has to be perfect. And who is taking that shot? Who is responding to the active shooter? More often than not it isn’t the SWAT sniper, it’s the patrol officer. And what do they bring to the fight? A patrol carbine. This is where short distance precision matters. This is where the LE-DMR concept started. A precision capable patrol carbine: tough enough for patrol, accurate enough for precision when it counts.

Now before we get into the details of the project itself, let’s make a brief diversion. Up to this point we’ve been talking exclusively in terms of law enforcement mainly because that’s where the idea began. This doesn’t necessarily exclude other applications. While defense of one’s family or home wasn’t the original idea there is certainly an application in that and other areas. After all, we’re talking about expanding the use and capabilities of the platform. So there may very well be all types of other folks who find value here.

Parts & Pieces

We’ll talk about them in more detail below, but to get started here is a partial parts list for the build:

- Barrel: 11.5″ LE-DMR prototype by Zero Theory

- Muzzle Device: Yankee Hill Machine Q.D. muzzle brake (cut down to two chambers)

- Gas Block: BCM, fixed, set screw type, steel

- Upper Receiver: Aero Precision, no forward assist

- Handguard: Advanced Tactical Ordnance, 10″, custom design

- Ejection Port Cover: Strike Industries Ultimate Dust Cover

Barrel

A key area for this project is the barrel. Here our priorities are precision capability and bullet performance at distances relevant to domestic law enforcement engagements. We want to be ready for a hostage rescue shot at 100 yards not a military engagement at 1,000 yards. If we can accomplish that with a short barrel, all the better. We gain something significant in terms of functionality in the patrol context. Giving up ballistic performance beyond several hundred yards simply isn’t relevant.

The heart and soul of a precision rifle is the barrel, especially for our goal of maximizing precision out of a short barrel. To do this we collaborated with one of the best precision AR barrel manufacturers in America, Paul Craddock, owner of Craddock Precision. What we came up with is an improvement on the 11.5″ 5.56 barrels we’ve been shooting for so many years. The reference LE-DMR barrel is spec’d as follows:

- Manufacturer: Craddock Precision

- Barrel Blank: Bartlein Barrels Inc

- Rifling: 5R cut-rifling

- Material: 416R stainless steel

- Twist: 1:7

- Crown: true 11-degree target crown

- Chamber: 223 Wylde, hand cut by Craddock Precision

- Length: 11.5″

- Gas system length: custom length “carbine plus one”

- Gas port: custom size, tuned to run suppressed with a fixed gas block and standard weight carbine buffer

We didn’t invent this barrel. Craddock Precision has been making variants of it for some time. The barrel’s design, the gas system in particular, is geared toward running suppressed with a fixed gas block. This met perfectly with our vision. We wanted a fixed gas block for durability and to avoid the additional variables associated with an adjustable gas block. We also wanted to run suppressed. One of the main reasons we specified a short barrel was to make room for a “k can” for working around vehicles. Craddock built this barrel the right length and with a custom designed gas system to run suppressed with a fixed gas block. It was a perfect fit.

In fact, we liked it so much we worked with Craddock Precision to co-brand it and are now the exclusive distributor. If you’re interested in picking one up for yourself, check out the LE-DMR product page or send us an email at info@zerotheory.org.

Handguard

Handguard

There are more companies making free-float handguards than you can shake a stick at, so to speak. We’re being choosy here. We wanted one with a steel barrel nut for increased rigidity. That eliminates many manufacturers, even some we thought of as “high end.” Also, we wanted a barrel nut design which did not require timing so the gas tube can wiggle freely inside the upper receiver.

Finally, we wanted no contact between the handguard and the receiver. That means no “anti-rotation” tabs, nubs, or otherwise. In the end, we went with a 10” handguard from Advanced Tactical Ordnance out of Abbeville, Mississippi. They made a handguard with almost everything we wanted. It did come with anti-rotation tabs, but they were happy to cut those off at our request. Their handguard also happened to have the cosmetic features we like as well: full picatinny top rail, M-LOK slots at 3, 6, and 9 o’clock, and built-in QD sling mounts.

The single thing we would change is adding a short integral picatinny rail section at 6 o’clock near the muzzle end, similar to the Geissele Mk4. This is where we like to mount a removable bipod. It should be easily remedied with the addition of an M-LOK picatinny rail section, but we’d prefer it be built in from the factory, especially since the gas block on the extended gas system of the LE-DMR barrel sits just above that location. In our mock up the M-LOK nuts are closer to the gass block than we’d like. In the final assembly if this becomes a problem we will have to find another way to attach the rail.

We’ve also considered a 15” over-suppressor style handguard. Ultimately we decided against it for the prototype upper because we couldn’t find one with all the features we wanted. We haven’t ruled out this option for future builds, but it wasn’t where we went with the first one.

Assembly

One of our considerations for this build is “stacking tolerances” where small variables are concerned. We’re paying attention to small details that normally go overlooked. For example, we’re eliminating as many points of contact with the handguard as possible. Below is a list of some aspects of the assembly process we’re keeping in mind.

- Handguard: Mounting the handguard with a small gap between it and the receiver where there is no contact between the two.

- Ejection Port Cover: We’re using an ejection port cover from Strike Industries which doesn’t use the traditional ejection port cover rod which normally makes contact with the handguard.

- Headspace: Proper headspace is important, so we made sure to headspace the barrel with the bolt we selected

- Torque Specs: Ensuring proper torque specs is a must, too much or too little torque is a problem for the barrel nut, muzzle device, and more.

- Retaining Compound: We’re using a retaining compound between the barrel extension and the upper receiver. Again, it’s all about rigidity.

Ammunition

Regarding ammunition, we haven’t made final decisions. At the front of the pack is the venerable 77-grn Sierra MatchKing. We’ve had positive results in the past, but we want to be open minded. We’re planning to test several brands and bullet weights. We’ll develop some custom loads as well. As usual, we expect handloads to provide the best performance, but in the end we will attempt to identify a commercially available cartridge which performs the best in terms of both external ballistics and terminal effects. Eventually, we will update this article with pictures of shot groups and gel block test results.

Optics

As previously stated, advancements in technology and manufacturing have improved the performance, and lowered the cost, of weapon system component parts. For optics, not long ago your choices were somewhat binary. Close range? Red dot or irons. Further out? Magnified scope. For a purpose-built rifle you could do one or the other but not both, at least not both very well. Lately, the Low Power Variable Optic (LPVO) has changed all that. No longer are you forced to choose between opposite ends of a spectrum. You can now have a riflescope which legitimately functions well at both contact distance and 500 yards. There is a lot more to say about LPVOs, but that is another article. For now, suffice it to say the LPVO is a good example of the technology that makes the LE-DMR concept possible.

For that reason, we’ll end up with an LPVO on this project. We’ll start, however, with a higher magnification scope for accuracy testing. After we’ve got enough data to demonstrate the rifle’s capabilities, we’ll switch over to the LPVO for field testing.

Status & Results

Status & Results

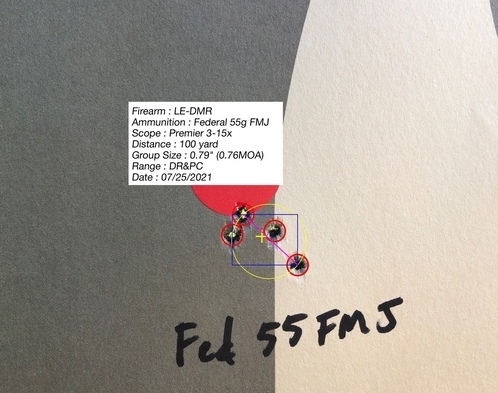

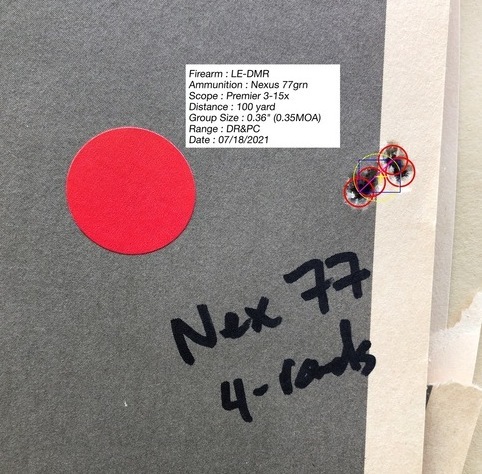

As of 07-25-2021, we’ve got the prototype assembled and about 200 rounds down range. We’re very happy with the way it came out. We had to get some custom work done on the handguard to accomplish the gap we wanted between it and the receiver. We also needed a little custom work to get the 6 O’clock picatinny rail section to mount securely without impinging on the gas block. Advanced Tactical Ordnance made quick work of both these issues and really helped us out.

For accuracy testing, we’re very happy so far. At this point we have a pretty good idea of the gun’s capabilities. In our hands the gun routinely groups sub-MOA and averages about 1 MOA at 100yds. That may not sound amazing, but it might be better than you think.

In our experience people tend to talk about their weapon’s capabilities with rose colored glasses, only remembering the best groups and flushing the memory of all those 2-3 MOA groups they wrote off as “that was me.” It’s similar to talking to someone about running. When you tell someone you ran an 8-minute mile, they’ll tell you about the time in college they ran a 5:45 mile. Sure thing bro. In reality, what happens if you ask them to show up at the track tomorrow? Odds are, they won’t be there. The same thing happens here. Every barrel manufacturer will talk about sub-MOA capability. But being capable of sub-MOA is different than averaging sub-MOA in field testing.

Averaging 1 MOA is harder than achieving 1 MOA. You have to routinely group below 1 MOA to make up for even a single group above 1 MOA and that is exactly what we’re doing. We’ve got a bunch of sub-MOA groups. We’ve even had 4-round groups at 0.35 MOA. We’re also not shooting in a laboratory. We’re running commercial ammo out of a short barreled semi-auto off a bipod in the Mississippi July sun. Lastly, we’re not discounting the 1.5 MOA groups because “I pulled that one.” Even with all that we’re still averaging 1 MOA at 100 yards.

Averaging 1 MOA is harder than achieving 1 MOA. You have to routinely group below 1 MOA to make up for even a single group above 1 MOA and that is exactly what we’re doing. We’ve got a bunch of sub-MOA groups. We’ve even had 4-round groups at 0.35 MOA. We’re also not shooting in a laboratory. We’re running commercial ammo out of a short barreled semi-auto off a bipod in the Mississippi July sun. Lastly, we’re not discounting the 1.5 MOA groups because “I pulled that one.” Even with all that we’re still averaging 1 MOA at 100 yards.

The recognized industry standard for a law enforcement sniper rifle is “averaging 1 MOA at 100 yards.” We’re not aware of an industry standard for DMR, but we commonly use “averaging 1.5 MOA at 100 yards.” That means this build is achieving sniper rifle performance in a DMR platform. So yeah, we’re pretty happy with it.

Like this? Check out our other articles…

[005] Quotes: The Man in the Arena

An excerpt from Roosevelt's "Citizenship in a Republic." Below [...]

[004] Maximum Point Blank Range

MPBR: what it is, how to find it, and [...]

[003] Fine Tuning Your Capabilities

Improving Data Collection Methods by Randy Davis [...]